|

|

|

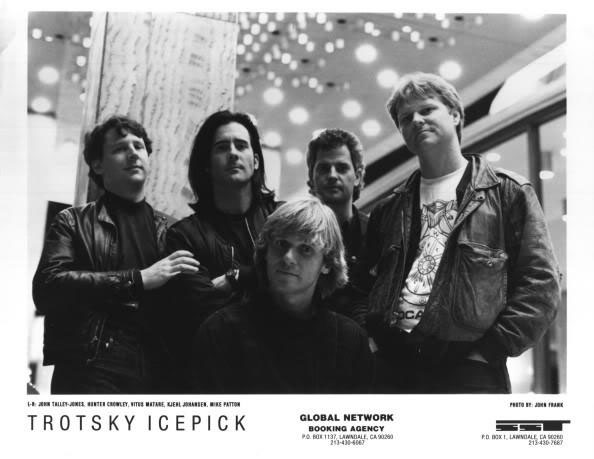

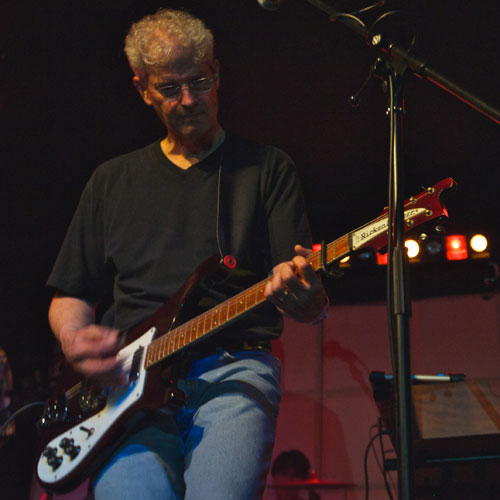

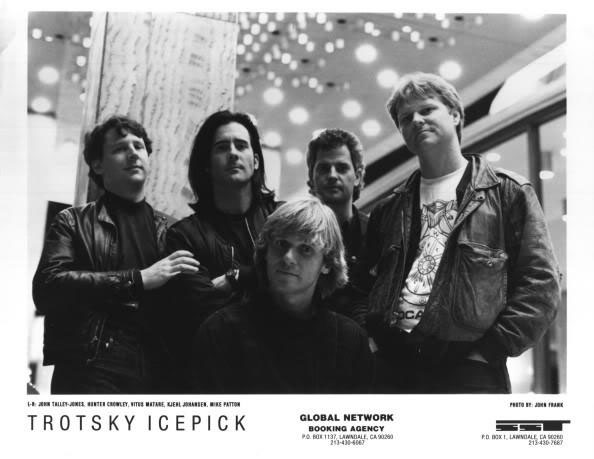

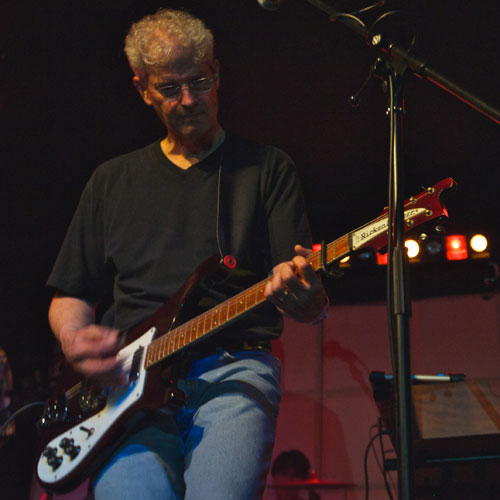

Kjehl Johansen is best known for his work with seminal art-punk band the Urinals/100 Flowers. He's also played with a host of other groups, notably Trotsky Icepick and Wednesday Week. His current band is the Circlons.

Kjehl Johansen met future Urinals bandmates John Talley-Jones and Kevin Barrett at UCLA in 1978. Galvanized by the burgeoning Los Angeles punk scene, the Urinals were also influenced by the brevity and erudition of art-punk act Wire. While many punk bands eschewed proficiency, nearly all followed orthodox rock song structures. The Urinals didn't. (After thirty years bassist John Talley-Jones still plays completely by ear.) What likely held the Urinals together was Kjehl's small amount of high school musical training and basic knowledge of guitar chords. Fellow UCLA student, and member of The Last, Vitus Matare turned out to be a crucial Urinals supporter, producing the band's recordings and showing them how to self-release records on their own Happy Squid imprint.

As the Urinals became more proficient as a group they decided to change their name to 100 Flowers. 100 Flowers' self-titled debut was released shortly after the band's 1983 demise. Alongside Vitus Matare, Kjehl formed Danny and the Doorknobs in 1983. (The band later changed its name to Trotsky Icepick.) Initially, Kjehl and Vitus shared vocal duties in Trotsky Icepick. Desiring a stronger singer, Vitus asked Kjehl's former Urinals bandmate John Talley-Jones to join the group as vocalist for 1989's El Kabong. Trotsky broke up shortly after 1993's live studio album, Carpetbomb the Riff.

The Urinals reformed in 1996, the same year Amphetamine Reptile put out the band's outstanding Negative Capability compilation of early singles and live material. Kjehl played with the group until 1998.

Throughout the early 2000s Kjehl focused on his solo material. He released two albums under his own name (Tower of Isolation and Pieman vs. the Light Bulbmen). Kjehl is currently wrapping up a new solo record with guest vocalists as diverse as Mike Watt and Lisa Kekaula. Trotsky Icepick is touring again and also finishing up their first new record in over twenty years. Finally, Kjehl has been busy with 100 Flowers. The group recently (January 2016) played a show in San Francisco at the Hemlock Tavern.

TB: Were you born in Los Angeles?

Kjehl: No. I was born in Dallas, Texas. My parents were born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. My dad wanted to start his own business, so he ended up in Texas. He supplied bedding and mattresses to mobile home manufacturers. My sister, who is three years older than me, was born in Sherman, Texas. The company my dad supplied products for went bankrupt, so he lost his business. We briefly moved to a bunch of different places as he followed work�Phoenix, Arizona, Nebraska and Michigan�before eventually settling down in Anaheim, California. I went from kindergarten through twelfth grade in Anaheim.

TB: Did you happen to go to Katella High School?

Kjehl: No. I went to Loara High School. I ran cross country and track so we'd have meets with Katella.

TB: Were you a music fan in high school or did that come later on in college?

Kjehl: It's interesting. My dad was a big jazz fan. He listened to two things: big band music and vocal groups.

TB: The Ink Spots?

Kjehl: Yes. He loved the Mills Brothers too. He was a big fan of barbershop quartets. But I didn't really start getting into music until my sister got into music. The first albums I bought were Live Cream and the second album by Blood, Sweat and Tears. We picked them up from a supermarket. I played clarinet in the marching band and all of my friends were into music. Progressive rock was popular when I was in high school. Jethro Tull, Yes, Genesis and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Led Zeppelin was around and so was Frampton. We'd see concerts at the Anaheim Convention Center and Anaheim Stadium. I was kind of into that scene. I ended up going to Cal State Fullerton for a couple of years before transferring to UCLA where I declared philosophy as my major. John (Talley-Jones) was a transfer student too. I met John and Kevin (Barrett) in the dormitories. That was when the whole punk thing was going on. The prog-rock thing was getting old. You'd get tired of going to stadiums to see bands. You could never actually see the band. The music was getting bloated. John, Kevin and I found out about punk together.

|

|

|

|

TB: Were you guys living in the same dormitory building?

Kjehl: Same building, same floor.

TB: That's really happenstance.

Kjehl: Yeah. I don't think John and Kevin were roommates for the first year, but we were all on the same floor. That's how we gravitated toward one another.

TB: Do you recall much about the first Urinals show at UCLA where you had Delia Frankel (vocals) and Steve Willard on guitar? I know you played a toy organ.

Kjehl: Sure. John, Kevin and I started hanging out. John and Kevin had met Delia and Steve Willard, who was the original Urinals guitarist. Steve actually knew how to play. He had a real amp and guitar. That was the circle of folks. I was looking for a place to fit in. John already had a bass; Kevin was on drums. Steve knew how to play guitar and I'm not much of a singer. So I thought, "Well, I'll just play keyboards." We found a toy keyboard�you'd press a button and it'd play chords. It had a few keys. But it really was a toy. We wrapped a microphone in a towel and stuck it in the back of the toy keyboard and plugged the mic into an amp. That's how we amplified the keyboard. I don't remember that many rehearsals. We were in the big cafeteria (on campus) that had a stage. This was for our dorm's talent show. We showed up with a set. We had two or three originals and a couple of covers. I know one of them was the Jam's "This Is the Modern World," which seems like such a long song for us. We were just struggling. We could only continuously play for about thirty seconds or a minute.

TB: That Jam cover is almost as long as two Urinals singles.

Kjehl: Yeah. The Jam song went on and on. I recall people looking at us like, "What the fuck is this?" Being a theater arts major, Delia was really comfortable in front of people. She did a great job. We just smashed through our parts. I still have pictures from that show. The whole punk thing was supposed to be serious and pissed off. I looked dopey in the photos. I was on stage smiling. It was fun. John has a recording of it.

TB: No way.

Kjehl: Oh yeah. It's very primitive. But the seeds are there.

TB: Was there ever talk of continuing the Urinals with Steve and Delia? I recall John telling me that Steve thought it was fun for a lark, but being much further along with his musicianship he didn't want to take it much further.

Kjehl: That's spot on. That's my recollection as well. The one thing about the Urinals � we all learned together. Steve already knew how to play guitar. He had fun but I don't think the Urinals was his thing. Delia had fun too. But I don't think she was very interested in getting into the music scene�playing in a band regularly and going to shows.

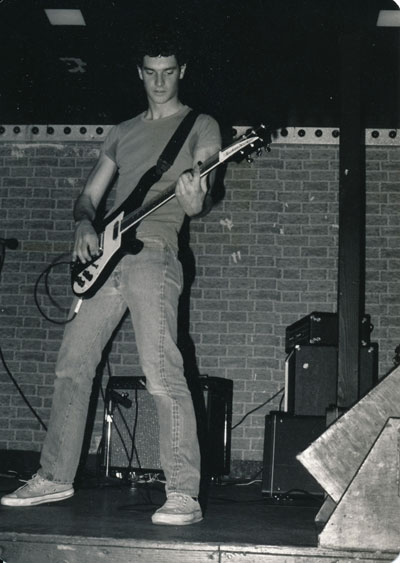

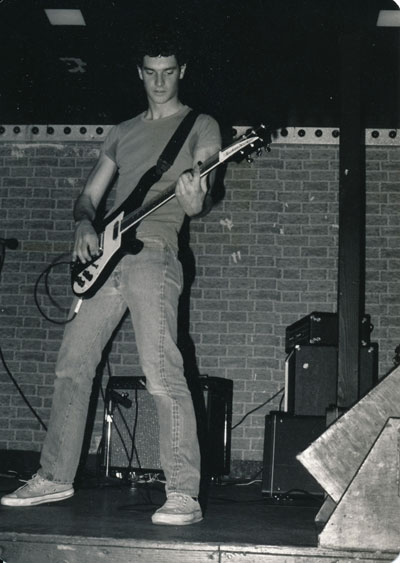

TB: Did you pick up your Rickenbacker 480 just after that show? It's a nice guitar and fairly uncommon.

Kjehl: There's an interesting story behind that one. Our first show (outside of playing at UCLA) was at Raul's in Austin. Kevin had borrowed a drum kit for it and John and I were playing these really badly made instruments we got at a pawnshop. We were in Austin�this is just before the show at Raul's�and I went to get some guitar strings at a local music store. In the window was that used Rickenbacker. It was relatively cheap: $350. Kevin was able to write a check to one of John's friends who cashed it. The bank manager approved it and we got the money. I then went back to the shop and purchased it. The only reason I got it was because Vitus (Matare), who had been helping us by that point, said, "Rickenbackers are great guitars." I remember I called him from Austin and told him about the guitar � what it looked like, the shape it was in and the price � and he said, "Buy it."

TB: The Huns and Phil Tolstead are pretty legendary around Austin. Do you recall much about that show?

Kjehl: I remember coming into the club and playing. I don't know if it was my insecurity, but I think the people there were more excited about the Urinals as a concept than by our actual performance. They saw us and went, "Yeah. Okay." I remember being really loud. We had never played with real amps before. The cops came around the back door and told us to turn it down or close the doors. Phil's band appeared much more proficient than we did. Phil was very animated. I remember watching them and thinking, "Oh, I guess that's what a real band looks like. Got it." (laughs)

TB: Your connection with Phil Tolstead and the Huns was through John Talley-Jones, who had gone to high school with Phil in San Antonio, correct?

Kjehl: That's right. We had a hard time getting booked in Los Angeles. Some of the feedback we got�I remember the guy who ran the Starwood said, "Man, I like your music but I just can't put 'The Urinals' on the marquee. What would people say? If you change your name we'll get you on a bill." We recorded a demo in one of our dorm rooms so we could get booked. We took it in and played it to one of the bookers at Club 88. He just started laughing. We were all pissed off and indignant. Years later John brought that demo out and played it at a party. I started laughing so hard noise wasn't coming out. I was just crying from laughter. Of course he [the booker] should have been laughing! We really had no idea.

TB: I guarantee you I'd love that demo.

Kjehl: Oh man. I did tell John, "One of these days, that demo does have to come out." I think it was a combination of our name and our lack of experience that hampered us from getting shows. Slowly we got more proficient and that helped us achieve more visibility. Word of mouth started happening from the people who saw us. I remember Craig Lee from the Bags saw us.

TB: Craig was a great writer.

Kjehl: He was. Craig called me up one day and said, "Hey, I'm interested in getting you guys on a bill. I want to come see you play." Craig caught one of our shows and we later did some gigs with the Bags. The Last were always getting shows and so Vitus would help us get on bills with them. We slowly started getting on our way.

|

|

|

|

TB: Vitus appeared to be incredibly supportive of the Urinals early on, getting you guys on bills and helping you record and release your own material.

Kjehl: I don't know what would have happened had Vitus not seen us at the dormitory that one time. You know how George Martin was the fifth Beatle? Vitus is the fourth Urinal. That's how I see him. Out of the blue he said, "I want to record you guys." He helped us with figuring out instruments. He helped John build his first bass by putting a new neck on it. He helped us both select amps and he encouraged me to purchase that Rickenbacker. Vitus would give us advice on live sound; he produced everything we recorded. Vitus also suggested we put out our own records. When he said that we went, "What? You can do that?" Vitus took us through the process of getting a single made step by step. He even helped us on the artwork.

TB: Through the Keats Rides a Harley compilation and the live material on Negative Capability, I picture you guys plugged into the Hong Kong Cafe scene with groups like Vox Pop and The Gun Club. Is that correct?

Kjehl: Yeah. I don't know how we got hooked into that scene. We'd go to the Hong Kong often to see bands. We played a lot of shows with The Bags, Black Flag, early Descendents, Red Cross, Wall of Voodoo and Human Hands. We got hooked into that scene too.

TB: The Pasadena scene?

Kjehl: Yeah. We felt comfortable at the Hong Kong. When bands asked us to open for them there, the place was usually packed. I think a lot of people saw us for the first time at the Hong Kong. We gained a lot of experience playing live there and it was one of my favorite spots.

It's funny. The first time we played there�the Hong Kong had an upstairs area where the bands would play and a downstairs area which was the restaurant�I remember looking around and noticing the tiles on the low ceiling. I thought, "These tiles look really familiar." It took me a couple of days to realize it, but when I was young and growing up in Anaheim, whenever my grandparents would come in from Chicago, we'd pile in the car and have dinner in Chinatown. The restaurant we'd go to was the Hong Kong Cafe. It was a really weird feeling realizing that the club we were playing punk rock at was the same place I'd go to as a kid to have dinner with my family.

TB: To this day, John plays by ear; he has no idea of where the notes are on his fretboard. That's a really interesting, instinctive approach, aligned with Eno, the Godz and John Cage. What was your approach to playing music in the Urinals like?

Kjehl: I had some musical training in junior high and high school, so I knew how to keep a beat and I knew when things were in tune and when they weren't. I had an ear. But I didn't pick up a guitar until I was twenty. We all started on our instruments at about the same time. Given my background, I knew scales and where the notes were on my guitar. But I didn't study music theory to play the guitar. Over the summer of 1978, I had picked up an acoustic guitar. This was in between the talent show we did as a five-piece and when we got back together as a three-piece in the fall when school started. A family friend, who was into jazz, gave me a few lessons. He showed me your basic first-position chords and barre chords based on E and A shapes. That was enough for me to figure out how to make sound out of a guitar�sound that wasn't just hitting open notes and being abstract about it. With bass, you can just play a single note. With guitar, you have to play chords. So I got a little help.

We didn't have a model. The prog-rock model was broken from our perspective. It was also too technical for us to even think about adapting to. We really had to think: "How can we write songs and play music?" For me, I just kind of floundered about, trying to figure out where to start. The thing that really opened it up for me was Wire's first album. "Okay, I don't need to play a fifteen-minute song or even a six-minute song. I can play a one-minute song or a forty-five second song. With my skill level, I can do that." The first song I wrote music to was "Hologram." It's two chords: G minor and B minor. I could play that. It gave me a path I could go down. John's writing was by ear. He has a really amazing sense of melody, and when he plays, he doesn't pick the obvious notes on bass. We recently had a Trotsky Icepick rehearsal and John started messing around on the bass. It just made perfect sense. What he was playing was exactly what John would do. No one else would play that part that way except John. When we were doing the Urinals, John, Kevin and I had many of the same limitations and some of the same inspirations. We sort of collectively pieced together a model we could work off of. Take "Ack Ack Ack." John had a bass note. Kathy (Talley) wrote some words. I still remember this�John came into my dorm room and said, "I've got this idea. Here's the bass part and some words. But it needs something more and I don't know what to do." I said, "Why don't you add another note here that's a half step lower?" And he said, "Yeah, that's great." So that's how we would write things. Someone would come up with an idea and you'd fill in a spot if it needed it. "I've got two chords. What can you do with it?"

TB:You can hear the evolution of the Urinals through the singles. "Hologram" is the starting point. You had progressed a lot by the time of "Sex."

Kjehl: Yeah.

TB: What gets sort of lost in the shuffle with the Urinals is Happy Squid Records. You guys did a great job with the label. It had an eclectic roster and Keats Rides a Harley is an exceptional compilation, featuring some of the earliest Gun Club and Meat Puppets tracks.

Kjehl: The way the label started was again with Vitus. He said, "Why don't you guys start up your own label to release your singles? I'll help you do it." We saved up all of our money and pressed up, I don't know, about two hundred copies of our first single. I remember discussing names with Kevin and John for the label. I tried to come up with the most inappropriate name for a label�the opposite of "Epic Records" or "Capitol Records." So we got back together and I asked, "Hey, how about Happy Squid?" And they said, "Yeah, we gotta do that one." It just doesn't sound like a record label. It was sort of making fun of major labels. We pressed up the first Urinals single. We got some gig money which we applied to the second (Urinals) single, recorded again by Vitus. Happy Squid was initially a vehicle for us. After the third Urinals single John asked, "What if we put out records by other bands?" Kevin and I said, "Yeah, that'd be great." So we started brainstorming who to ask. It was really organic. We released material by a lot of the folks we were playing with like the Meat Puppets, Human Hands and Gun Club. We thought, "Jeffrey Lee Pierce's band is pretty good. I think we could get Vitus to record them (for the Keats Rides a Harley compilation)." Vitus recorded the early releases with the exception of the Meat Puppets. The Meat Puppets sent me their tape to my home address in Anaheim. It was on quarter-inch tape and it was wrapped around a Super 8 film hub. They stuffed it in one of those cardboard boxes Super 8 film was sold in. I don't know where they recorded it, but it's amazing and really raw. Talk about a snapshot of where they started. I think the first release we did that wasn't a Urinals release was the Happy Squid Sampler.

|

|

|

|

TB: That's right. That was your fourth release on Happy Squid (1980).

Kjehl: We (the Urinals) all switched instruments and brought in someone else � my roommate Joel � and improvised. And that was the Arrow Book Club. There was some other stuff on there. There was a track by Vitus and John Frank called Danny and the Doorknobs.

TB: This was before you joined Vitus in Danny and the Doorknobs, correct?

Kjehl: Right. I think John Frank and Vitus put together a little quickie 4-track recording, a song called "Melody."

TB: How did you get acquainted with artists like Phil Bedel and Brent Wilcox?

Kjehl: With Phil Bedel, Neef and the more experimental stuff on the label�that was definitely John who brought that work to the attention of the band. John had a lot of interesting, non-mainstream tastes. It helped expose us to different things. John and I have talked before about how the music scene back then was all over the place. There were a lot of different sounds coming out, all falling under the "punk umbrella" for lack of a better word. You knew it wasn't prog, blues or straight-ahead rock 'n' roll. But it was vital and interesting music and there was a space for it. You could have a lot of different bands on the same bill: Human Hands, Wall of Voodoo, Gun Club, The Last and The Urinals. The music sounded very different but we found a scene where it all fit in and was accepted by people. It was a lot more wide open.

TB: John mentioned to me that the name change from the Urinals to 100 Flowers was inspired by your changing sound and a desire to distance yourself from the burgeoning hardcore scene. It was thought that the name "The Urinals" would confuse people new to the band into thinking you were a hardcore group.

Kjehl: Yeah. I think there was a sense that we were a very different group from the one we started out as. We thought changing our name would be a much more honest reflection of who and where we were at as opposed to continuing to call ourselves The Urinals. There's two theories as to why we named ourselves "The Urinals." The first one is that it literally means toilet. The other is that it has a connection with Dada and Marcel Duchamp. We sort of flirted with both of those meanings. But I think calling ourselves the Urinals had more to do with being direct and shocking. 100 Flowers is a little more abstract, which I think our music was becoming. It was more conceptual, albeit a three-piece and still minimal. There were more than two chords to our songs and less screaming. There was this hardcore scene coming up. Although we had roots in it and played with other bands who had roots in hardcore, we were staking out a different area. It just sort of naturally lead to us changing our name.

TB: Do you recall how long you were playing as 100 Flowers before you folded up?

Kjehl: I don't. I want to say that about half the time we were the Urinals, the other half we were 100 Flowers. That's a rough guess.

TB: I know the (self-titled) 100 Flowers LP came out after you guys had broken up.

Kjehl: That's correct. It took us a long time to get it out, even though we had had it finished for a while. That was part of the problem. We wanted the record to come out and it needed to come out. But as far as working together, we just couldn't manage that anymore.

TB: You cut the 100 Flowers record at Radio Tokyo, right? Was the first time you had been in a real recording studio?

Kjehl: We recorded about half of the album on 4-track with Vitus. We then got an invitation from Bemisbrain Records to come in to a studio and record some material. It was one of those deals where we recorded three tracks, kept two, and the other one went to Bemisbrain for a compilation (Hell Comes to Your House) that they were releasing. We did "100 Flowers," "Reject Yourself" and one other track. We were surprised by the results. It sounded powerful and you could really hear John's voice. John's got a great voice. At that point I said, "Hey, guys, why don't we try to a record an album on 8-track?" There was some debate about it�"Well, we've already recorded half the record already. But it does sound good (on 8-track)." That's when we switched over and went to Randy Burns at Orange County Recorders. We did do a couple of tracks at Radio Tokyo. We did the "Presence of Mind" single there�"Poltergeists at Home" and I can't recall the other track. Eventually, "Presence of Mind" and "Poltergeists at Home" did end up on the 100 Flowers LP, although they were recorded at a different (Radio Tokyo) studio. Everything else was recorded at Orange County Recorders.

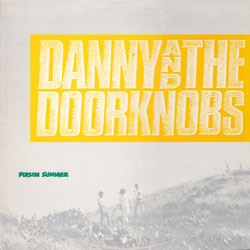

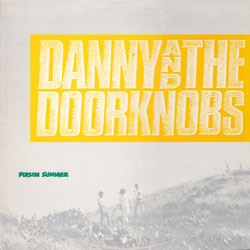

TB: The first Danny and the Doorknobs LP (Poison Summer) is one of the great unknown records from the early '80s (although recorded in '83, it was released in '86). "In Exile" and "Northern Lights" are great tracks.

Kjehl: We had a lot of fun. We started on the record around the time Vitus was having difficulties with Joe Nolte of the Last. I had left 100 Flowers. We both wanted to make music, so Vitus suggested we get together to see if we could come up with a few ideas. Vitus had already been playing with John Frank. We went into Ethan James' studio, Radio Tokyo, and Vitus traded Ethan a Marshall half stack cabinet for recording time. So we recorded a bunch of music there. Vitus then built a home studio. We did the overdubs (for Poison Summer) at Vitus' house. We didn't have any songs written when we went into record. We just recorded the music and then we came up with the bass parts, the lyrics and everything else afterwards.

TB: You got really incredible results for such an impromptu record.

Kjehl: I had never done anything like that before and I don't think Vitus had either. It was a really cool experience.

TB: Trotsky Icepick's discography can be a bit confusing to folks new to the band.

Kjehl: I guess the first precursor was Danny and the Doorknobs. We decided to turn that project into a real band. Vitus came up with the name Trotsky Icepick. As Vitus explains it, Trotsky Icepick is slang for when a soundman pushes the faders all the way up at a sound check, causing excessive feedback through the monitors; you get that right in your ear and it hits you like an icepick.

|

|

|

|

TB: Soviet assassin soundmen. I always wondered how that name came about.

Kjehl: Yeah, when that would happen, Vitus used to say, "Thanks for the Trotsky icepick." We also had another joke: "Trotsky Icepick: the ultimate earache." We needed folks to round out the band. Jamie Lennon, our drummer John Frank's friend, came in and played keyboards and keyboard bass. That filled out our sound for recording and for live shows. The first album was called Poison Summer by Danny and the Doorknobs. Vitus came up with the idea of keeping the name of the albums the same but changing the name of the band for every release. Of course, the opposite is almost always the case: you keep the band name and change the names of the records. The second record is Poison Summer by Trotsky Icepick. We ran into the problem of having a couple of releases, we were playing shows, and it felt like we might be throwing it away with the name changes. The concept lasted two albums. We joked about changing the name a third time, but never followed through on the threat.

TB: What was Trotsky Icepick like early on, before you signed to SST? Was it more of a side project?

Kjehl: It was the only music project that I was involved in. I believe it was also the only music group the other members were involved in as well. It wasn't a side project. Part of the difficulty was that, as we were doing Danny and the Doorknobs, I was still in law school.

TB: That's brutal.

Kjehl: Yeah. I just didn't have a lot of time available around then. When I passed the bar and got a job, that's when Vitus and I started playing again and taking it more seriously. That's when we came up with the second Poison Summer album (by Trotsky Icepick). We played at Texas Hotel Records�a little shop in Santa Monica. We played at Club 88, Club Lingerie and a few other places. We were playing shows regularly but not pushing it as hard as The Last, the Urinals or 100 Flowers. But after the second record had come out and some gigging, I don't think Vitus was happy with the direction of the band, so he dissolved it. But we still wanted to go forward. That's when we recruited a new drummer (Jason Kahn) and bass player (John Rosewall) for the Baby (1988) album. That's where we started playing more�getting on more bills, doing some light touring. SST was also interested.

|

|

|

|

TB: Baby is one the first records you recorded that actually spanned a long period of time. You had guests like DJ Bonebrake on it as well.

Kjehl: Right. Vitus had a home studio that we used for rehearsals. We'd get together periodically and record a backing track here, an overdub there. It was spread out over a period of time, rather than knocking it out in six days.

TB: You guys had a formula that was working for you and then John (Talley-Jones) joined on El Kabong. It makes sense that he came in � John's a great vocalist � but it was still a bold move a few albums in.

Kjehl: (laughs) Not to dump on Vitus too much, but he was first among equals. We were partners starting the band, but he was older and more experienced.

TB: The Last were pretty successful around the time of LA Explosion too.

Kjehl: Right. I think people naturally looked to Vitus as the band leader. After the second Poison Summer album, when he said that we were going to get a new lineup together, I was like, "Oh, okay, Vitus." After Baby, he said, "I'm firing you and me as singers; we can't sing very well. We need someone better." I said, "I'm really starting to get used to singing." Vitus replied, "No, we're lousy. We need to bring someone else in." "Oh, okay, Vitus." I didn't have much input on it. It was difficult for me. John and I weren't completely over our past band issues. It was a little awkward. But with Vitus and the other guys there, it wasn't the same dynamic as me, Kevin and John. It made it easier. But it wasn't completely resolved. It was sort of an experiment: "Is this going to work?"

TB: As an outsider looking in, Trotsky Icepick appeared to be a fun band to be in. From Monochrome Set and Magazine covers to songs about clowns and Marshall McLuhan.

Kjehl: There was definitely a lot of freedom. SST left us alone in terms of what we came up with. That was great. Coming from the Urinals and the Last, it really encouraged an "anything goes" approach. It shouldn't be surprising that Vitus, John Talley-Jones and I�as the principal songwriters�came up with such varied material. John did a great job in Trotsky. He stepped up to a difficult situation where he wasn't really a part of the music writing process. The songs were finished and sort of given to him, and he was left to figure it out. John's a great lyricist and performer. Vitus obviously made the right call. Bringing John to the band added to it. Not that Baby wasn't great and not that we couldn't come up with another good record. We kept making big changes on each record, starting with the first Danny and the Doorknobs LP. It was fun and really challenging.

TB: You kept changing it up. The Ultraviolet Catastrophe (1990) was a more polished record. The next record, Carpetbomb the Riff (1993), was your most rocking album.

Kjehl: That reflected personnel changes. Our circumstances changed as well. We didn't have access to the studio as much, so a lot of The Ultraviolet Catastrophe was recorded at the studio set up in my apartment. Vitus wanted different musicians to come in to expand our sound. So we got an accordion player and someone to play the Chapman Stick. We tried everything on that record. When Mike Patton came in on bass and Skippy Glogovac rejoined on drums (for Carpetbomb the Riff), it was definitely a more hard-rocking approach. It changed the direction of the band yet again. That sound fit that lineup.

TB: Was Trotsky Icepick starting to tour more near the end of its initial run?

Kjehl: Yeah. I think Greg Ginn and SST felt like, "We like you and you guys are putting out good records. But you've got to get out more on the road if you want us to keep putting them out." We were reluctant tour guys. We did jump into touring with both feet in '91 and '92. We did one of those twenty-nine shows in thirty-one days deals in a pickup truck.

TB: Still jamming Econo with a law degree!

Kjehl: Fortunately, I had a real flexible work schedule. I had accrued enough time off for a leave of absence. They were really accommodating.

|

|

|

|

TB: Hot Pop Hello (1994) was posthumously released, wasn't it?

Kjehl: That came out after the last Trotsky tour. Carpetbomb the Riff was kind of tough. Vitus was there for the recording, but after we finished he said, "I can't do it anymore." So we went out on the road as a four-piece. Unfortunately, Mike (Patton), our bass player, couldn't play in the band any longer; he had a couple of kids and needed to stay close to home. So we lost Mike at the end of the tour. We did one or two shows as a three piece. We had the last record in the pipeline before the last tour, so SST put it out as we were wrapping it up.

TB: Amphetamine Reptile put out Negative Capability in 1996. It was surprising to see the Urinals reform.

Kjehl: I read your interview with John (Talley-Jones) the other day and I think he recalled that period pretty well. It was a record release party for David Nolte and his wife Kristi (Callan) that got the Urinals back together. David said, "Too bad the Urinals aren't together. We'd love to have you on the bill." Things had thawed enough between me, Kevin and John. I made a call and asked them if they'd like to play the show. And they said, "Yeah, let's give it a shot." The show went well enough for us to decide to keep playing. It went from there.

TB: By that time, I think people really caught up to what you guys were doing and about.

Kjehl: It was kind of strange the second time around for me. The only shows we ever headlined (during our initial run) were our last two at the Anti-Club before we broke up (in 1983). People were interested in us, we had carved out our own niche and had recordings. But I didn't feel we were on the same level as X, The Bags or Circle Jerks. Over time, it felt like the audience had come up with a different assessment of us. What was the joke Mission of Burma had when they reformed? "Hey, you're a lot nicer to us than your parents were." There was more interest, visibility and opportunities for the Urinals when we reformed (in 1996). We went to Seattle and opened up for Mudhoney. We got to open for Sonic Youth. That was nice to experience. Every time something cool would come our way, I felt like saying, "We'd love to do it. But you know we're the Urinals, right?" We just laughed and rolled with it.

TB: After your second time around with the Urinals, you did a couple of solo records. One on Avebury records and one you self-released, Tower of Isolation (2001).

Kjehl: Right. I did an EP called Pie and Isolation. I also did a solo record called Tower of Isolation. An old friend named Don Williams and his wife Kelly (Callan) had a label (Avebury) and said, "Hey, why don't you do a box set?" They helped with the packaging. We did a very limited run�I think 100 copies and we numbered them. I did a small number of shows with my band to promote it. I'm still working on the world's longest follow-up solo record. I've been working on a double album with the same guys. Hunter Crowley on drums, Tom Hofer from Trotsky Icepick on bass and a guy named Steve Andrews on guitar. Steve had a brief stint in the Last. The idea for this most recent solo album came from Don Williams. Don said, "You know, you really can't sing." It was reminiscent of Vitus. "You need to do an album with different singers on each track." We've got about twenty tracks. Kira Roessler and Mike Watt sing on a track. Chip and Tony Kinman from the Dills, Keith Morris and Steve Wynn sing on tracks. Kristi Callan (who I played with in Wednesday Week),John Talley-Jones, Barbara Manning, Jack Brewer, Michael Quercio (from the Three O' Clock) and Jeff White, the current singer of Human Hands, sing on different songs as well. I was really happy to get Lisa Kekaula to sing on a track. She did an amazing job. A few more folks contributed (vocal tracks) as well.

TB: This is stuff you cut with your backing band the Circlons, correct?

Kjehl: Yep. We're finishing up the Trotsky album and I'm trying to finish up the Circlons album. I'm hoping to get it out in the new year. We're almost done with both records.

TB: What's the deal with Trotsky Icepick? I'm not living in the Los Angeles area anymore, but I still see you're playing shows from time to time.

Kjehl: Definitely. We've backed off on shows for the last two to three months just so we can finish up the new album. We've been playing some clubs around LA.

TB: Part Time Punks at the Echo.

Kjehl: Yeah. Punk Rock BBQ at Liquid Kitty. The Redwood Bar in Downtown. Cafe Nella on Cypress Park is a great venue. We've threatened to go up to San Francisco or down to San Diego. We decided if we're going to do that, we need to have an album out to promote it. That's the latest.

|

|

|

|

END INTERVIEW

Kjehl's bio on Avebury Records.

The Urinals online here.

Happy Squid online here.

Read Ryan's interview with John Talley-Jones here.

Urinals photos courtesy of John Talley-Jones

Trotsky Icepick band photo courtesy of Tom Hofer

Trotsky Icepick live photo courtesy of Kevin Gilligan

Interview by Ryan Leach, 2015.

To read other TB interviews, go here.

|

PREVIOUS PAGE � HOME � NEXT PAGE

|